Along with Puerto Rican novelist Jonathan Marcantoni, he runs the YouNiversity, a non-profit digital workshop that provides students access to and experience with the publishing industry through media professionals in the United States, Europe, Latin America, and Africa. Unlike the curriculum and objectives of many MFA programs across the United States, the YouNiversity focuses on several different facets of a writer's literary development, including real-time interaction with editors, literary agents, graphic artists, publishers, and other readers and writers.

Campanioni's work is affiliated with the Latin American neo-Surrealists along with Brion Gysin and his cut-up technique.While also influenced by the historic avant-garde (Dada, et al.), the coterie that haunts his first trilogy of novels is the Situationist International.

His writing responds to the disintegration of language and consciousness; an attempt to suggest a new way of communicating, which is still taking shape. Campanioni has referenced quotes from William Burroughs to describe his own writing process in interviews, including the emphasis on displacement: "I wrote a trilogy out of order and then rearranged it, because the whole of life is like that--a cut-up--and when you cut into the present, the future leaks out."

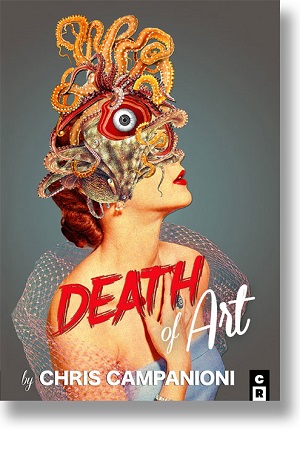

His hybrid nonfiction/poetry book Death of Art (C&R Press) was celebrated as "bringing surprise and joy back to Conceptual writing", and "a striking amalgamation of memoir and social critique, poetry and cultural theory."His poem "Transport (after 'When Ecstasy is Inconvenient')" was a finalist for the Zócalo Public Square Poetry Prize in 2015, awarded annually to the U.S. poet whose poem best evokes a connection to place., In March 2014, Campanioni became the youngest finalist for the International Latino Book Awards when Going Down was selected as Best Debut Novel.

Minor Literature(s) 2015 review of Campanioni's recent work focused on his parents' immigrant past and his own dislocated present, asserting that his poetry had found ways to re-evaluate technology as a conduit for connection and learning, especially linguistically.

The New York Post named Going Down one of its "must-read books" of the month in October 2013.

Going Down has been lauded by various media, including the Manhattan Times, for its realistic portrayal of the newsroom and the fashion industry from the Latino perspective.The novel has also garnered criticism for its dark tone and confusing meta-fiction writing style.

In the spring of 2013, Campanioni was awarded an Academy of American Poets Prize for selected poetry. From Susan L. Miller and the Academy of American Poets committee:

"Campanioni immediately draws the reader in with a sharp sensibility for the music of language. 'Forty faces, one line' demonstrates an aptitude for poetic structure as well as a contemporary sense of rhyme, and 'Billboards' focuses first in a prose-poem, then in quatrains, on the contrast between the self commodified and the loneliness of the soul inside of the commodified body. By focusing outside and inside the self in refreshing ways, Campanioni offers us meditations on 'body and soul' that include the elegant woman who’s dropped her dentures as well as the child yearning to eat cake.

The poem 'Endnotes for Life' takes familiar territory (the story of Lot’s wife, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, and the personal narrative) and makes a structure for it that calls into question the primacy of narrative in much American poetry. These sharp views of the human theater force us to examine our place in it, and to question what more exists in our own internal worlds."

His poetry, fiction, and nonfiction has been published in The Brooklyn Rail. Word Riot, Numéro Cinq, Fjords Review, San Francisco Chronicle, The Star-Ledger, The Record (Bergen County), Across the Margin, tNY Press,Literary Orphans,,Blunderbuss Magazine,,Rosebud Magazine, Ambit, Gorse, RHINO, Quiddity, Prelude,Carbon Culture Review, and elsewhere. As an actor, he has also appeared on “The Today Show,” “The View,” and in various speaking roles on “All My Children” and “One Life to Live,” in addition to commercials ranging from Dentyne Ice to Axe body spray, Ab Roller Evolution and Rocking Abs. He has been photographed for international magazines, books, and catalogues spanning Rio and Milan, Paris and Melbourne, including the cover of DNA.

Chris Campanioni seeks to blur boundaries. He is an author, teacher, journalist, and model, and the co-editor of PANK, Tupelo Quarterly, and At Large Magazine. He gravitates toward anything that involves creative thinking, learning and teaching, writing and editing, and most importantly, connecting with people. Campanioni’s debut novel, GOING DOWN, was selected as Best First Book at the International Latino Book Awards in 2014. His poem “Transport (after ‘When Ecstasy is Inconvenient’)” was a finalist for the Zócalo Public Square Poetry Prize in 2015, awarded annually to the U.S. poet whose poem best evokes a connection to place. In 2013, he was awarded an Academy of American Poets Prize for selected poetry. His new book is DEATH OF ART (C&R Press).

Campanioni is a member of the National Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, the Academy of American Poets, SAG/AFTRA, and the Dow Jones Newspaper Fund. His non-fiction, poetry, fiction, and criticism have appeared in the Star-Ledger, San Francisco Chronicle, The Brooklyn Rail, Prelude, RHINO, Handsome, Ambit, Gorse, RHINO, Quiddity, DIAGRAM, and several other journals and anthologies, including the London Journal of Fiction, America Is Not the World, and Sundress Publication’s MANTICORE: HYBRID WRITINGS FROM HYBRID IDENTITIES.

Campanioni has lectured at various academic conferences and events, in person and via video, including the Art of Outrage, TED Talks, and the Transatlantic Poetry Series, and has served as a visiting author and speaker at universities across the United States, which are currently teaching or have taught his work. He was awarded a Graduate Assistantship and a Presidential Scholarship before completing his MA in English literature from Fordham University in the spring of 2013, graduating summa cum laude. Today, he is a Provost Fellow and MAGNET Mentor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he is conducting his doctoral studies in English. He also teaches literature and creative writing at Pace University and Baruch College.

Writer Chris Campanioni gives a crucial glimpse into our modern narcissism with his new book of memoir / non-fiction / hybrid text / does it really matter, Death of Art. Despite the ostentatious title, Campanioni tactfully avoids repeating oft-argued cliches regarding art’s apparent demise, and instead uses the title as an entry point for talking about identity, language, social media, and modern life as a kind of performance.

The book begins with Campanioni sitting around with a stranger cutting his face out of magazines in which he modeled. The book follows this act of self-immolation throughout, as Campanioni struggles with trying to refashion his own image and his own identity, in a world where these things are valued above all else. Campanioni is frank and open about his stints as a model and actor, and his struggles with the performative aspects of both.

The text almost becomes a space where Campanioni can explore himself; a liminal space where he can avoid binaries and social norms and—in a way—deconstruct himself:

I had lately been thinking of a project titled Death of Art, which itself came from the blacked out title of a poem I’d just written called ‘Death of the Artist…’ Cutting out my face could be the beautiful overture.Formally, Death of Art moves from vignette style passages of memoir, to essays and poetry. Campanioni’s tone alternates from playful, to philosophical, to the banal and the confessional, and all at a blistering pace. His subjects range from 90210 and Tinder dates, to social media narcissism and celebrity culture. An obsession with 90210 and a brief reference to Care Bears in particular become interesting pivot points for Campanioni to make comparisons between the empathy of our former analog world, and the disconnectedness of our modern digital world.

Death of Art brilliantly taps into our insatiable need to be seen and felt via social media, and how life is not experienced in our modern age, but rather, documented. The Facebook photo as preferred cultural currency to the actual image and experience represented.

The same way that our generation will look back on our lives in sixty years and there will be plenty to see. Probably we only wish we would have lived it too.In the section titled “Self-Interested Glimpses,” Campanioni adopts an essay style (as he frequently does) and argues that “Authentic experience has been replaced by fetishized experience; existence becomes object.” In Campanioni’s world, the Instagram photo of a sunset now reigns supreme over the actual sunset. This is not a wildly new concept, as many postmodern thinkers have believed that society and modern culture have started to place more importance on “simulacra” or the simulation of reality, rather than the object itself.

For Campanioni public spaces have become zones of anti-social behavior. He argues that the increased access to each other that social media provides us has “led us to become less tolerant, less sympathetic, and less understanding.” This is exemplified in the book via the nearly tweet sized entries describing a series of Tinder dates where he struggles to make eye-contact and prefers to meet in coffee shops, hotel bars, or “anywhere public enough to pass through, in transit, like anyone else. Just passing through.”

Much of the book is devoted to Campanioni’s self-reflection and almost reads like some playful postmodern diary. The author is constantly engaged in a dissection of his own image, striving and hoping to dismantle it. “The Internet has its own idea of me, and so do its worshippers. I want to create my own idea of me. Maybe the Internet will follow.”

Campanioni’s concept of life being fetishized but not experienced, is nicely juxtaposed with passages that reflect his childhood:

We lived our days as if they were scenes in a musical; we danced & continued to sing. Sometimes in Spanish or English but also often in a language made up by my father, a practice I’d adopt too, & which became my true joy in life: the pleasure of words & the sounds they contained. Whether it meant anything was besides the point; it meant everything.Here childhood is reflected upon nostalgically and without the author’s jaundiced view of our current culture’s unchecked narcissism. It’s also indicative of Campanioni as a great linguaphile, and the simple pleasure he derives from the physical sensation of the words exiting his mouth. This runs counter to the mechanized way we communicate now:

Face-to-face meetings have given way to my face on your touch screen…Death of Art is a punchy hybrid text that holds its own intellectual weight and does well to not veer off into pretension nor cliche, which is no minor triumph considering it’s broad and aspirational title. Campanioni is a serious writer and a world class thinker, and there is something great to be gleaned from his latest offering that seems to revel in its ability to avoid classification and open up a dialectic about the modern ways in which we communicate.

Writer Chris Campanioni gives a crucial glimpse into our modern narcissism with his new book of memoir / non-fiction / hybrid text / does it really matter, Death of Art. Despite the ostentatious title, Campanioni tactfully avoids repeating oft-argued cliches regarding art’s apparent demise, and instead uses the title as an entry point for talking about identity, language, social media, and modern life as a kind of performance.

The book begins with Campanioni sitting around with a stranger cutting his face out of magazines in which he modeled. The book follows this act of self-immolation throughout, as Campanioni struggles with trying to refashion his own image and his own identity, in a world where these things are valued above all else. Campanioni is frank and open about his stints as a model and actor, and his struggles with the performative aspects of both. The text almost becomes a space where Campanioni can explore himself; a liminal space where he can avoid binaries and social norms and—in a way—deconstruct himself:

No comments:

Post a Comment