THERE are a lot of things that never make it into memorials, and

maybe they were never important to begin with. Like seeing the director

and fugitive Roman Polanski sitting beside a beautiful dark-haired woman

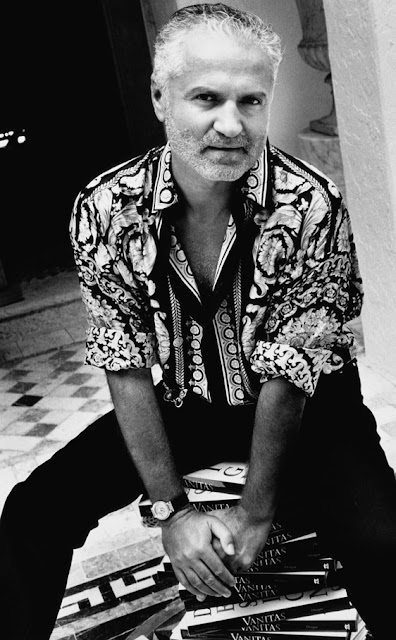

at a Gianni Versace

show in Milan. This was around 1990 or 1989, and the reviews of

Versace’s collections were filled with a tone of moral indignation at

the idea of supermodels in bondage dresses, when, honestly, everyone in

that grim city should have said, “Why not.”

I tapped on Mr. Polanski’s shoulder. I didn’t want to miss an

opportunity to speak to the director of “Chinatown,” but I couldn’t

think of anything to say. So I made some patently self-evident remark

about the show and then, looking at the woman, said something like “you

and your girlfriend ...”

Mr. Polanski’s face went cold. “She’s my wife,” he said, and turned away.

So. You can say that it doesn’t matter that I didn’t recognize the

actress Emmanuelle Seigner, or that he shouldn’t have been so touchy,

but since the memory also involves Gianni Versace, it seems to me that

this conclusion may be beside the point.

A lot has been lost in the

decade since Versace’s death in Miami Beach — a great talent, most

visibly. Try to imagine your wardrobe without the jolt of a print, the

vitality of a stiletto, the glamorous bric-a-brac of chains and doodads.

This was Versace’s doing. His influence melted and spread far beyond

the sexual heat of his runway.

Yet all the minutiae that go into

making up an account of a person’s life — what if that is lost? Versace

introduced us to a personal and vaguely disrespectable world of rock

divas and legends, and it is all that ephemera that now floats in my

head.

Well, what does matter? If it’s the latest brand-building effort or a celebrity with her purchased adoration, then we are in trouble.

Reading accounts of his life and death that have appeared on this 10th

anniversary — he was murdered July 15, 1997 — I am struck by how much at

a remove they are from the subject and the events of that terrible and

strange week. The facts are all there, neat as buttons, but the

perspectives are those of outsiders. And it’s not the fault of the

Versaces.

A year before the murder, Graydon Carter, the editor of

Vanity Fair, where I worked at the time, asked me to write a profile of

Versace’s sister, Donatella. Despite rumors of a sibling rift, I don’t

think anyone considered Donatella, then 42, a serious rival. The

Versaces were spending a fortune — $6 million for a Miami Beach

property, Casa Casuarina, $7 million for a New York town house filled

with Picassos and Rauschenbergs — and Donatella, with her blaze of

diamonds and yellow hair, was another way to illuminate their lifestyle.

The

article ran in the June 1997 issue, one of several magazines that

Versace’s killer, Andrew Cunanan, who was obsessed with celebrity,

bought around the time he arrived in Miami. On the morning of the

murder, Maureen Orth, a senior writer at Vanity Fair, was in the

fact-checking stages of a 10,000-word article about Mr. Cunanan, who was

already suspected in four murders in Minnesota, Illinois and New

Jersey. She immediately had a hunch it was Mr. Cunanan who shot the

designer on the steps of his home as he returned from the nearby News

Cafe on Ocean Drive, and said so to Mr. Carter.

I was on

Nantucket, where the phone was ringing with calls from news

organizations — CNN, the BBC — seeking information about possible

tensions within the Versace family. The murder had thrown a weird light

on a world people knew very little about. By midafternoon, Mr. Carter

decided that Ms. Orth and I should go to Miami. If the killer was Mr.

Cunanan, the story would be hers.

I first met Donatella in June

1996 in Milan, in the 21-room apartment where she lived with her

husband, Paul Beck, and their young children, Allegra and Daniel.

That

night, though, it was just the two of us for dinner. She took me into

her dressing room, throwing open the closet doors. This is for bags, this is for shoes. I thought she seemed as nervous as a cat.

But in August, when we met again at the house in Miami, she was at ease

— and fun. I brought my son, Jacob, who is Allegra’s age, and they swam

in the turquoise pool, where Donatella, for one of Madonna’s birthdays,

had floated a huge cake.

She took me around the Spanish-style house,

pointing out Gianni’s private rooms, which overlooked Ocean Drive, and

the room where Jack Nicholson had once stayed. We had lunch in the marble dining room. Elton John phoned.

Yet, as extravagant as everything was, what impressed me most was how

protected Donatella was by the screen of her brother’s fame and talent.

She was completely free to dazzle, a living Medusa. I won’t say she was

innocent — the Versaces were never innocent. But she possessed a

fragility and a candor that helped to mediate the more implausible parts

of her existence.

Later, we all went out to the beach, Donatella

in a chartreuse bikini and a big canary diamond. Around 1 p.m., a man

from the house wheeled a cooler across the sand. It was loaded with

freshly grilled hamburgers and chicken sandwiches.

On the day

after the murder, I stood in the throng of news people gathered opposite

the house — a surreal experience. The story was Ms. Orth’s; Mr. Cunanan

had been identified as the killer and was at large. You felt that a

kind of lunacy enter those already lunatic streets, clogged with

tourists and gym queens and now reporters, all moving toward 1116 Ocean

Drive. I remember at 6:30 a.m on the third day of the manhunt, Ms. Orth

and I walked from the Raleigh Hotel down to the Versace mansion. A crowd

was already gathering in the muggy heat.

Several times I phoned

the house, reaching Ed Filipowski, a publicist who worked for the

Versaces. But the family wasn’t saying anything. Ms. Orth and I pursued

leads. They were all pretty seedy: a north-beach gay hustler bar called

the Boardwalk, where Mr. Cunanan had been seen before the murder, and

the $36-a-day hotel where he had stayed when he got to Miami. This was

the side of the strip that Mr. Cunanan revealed, before he killed

himself on July 23.

The murder exposed the financial

vulnerability of the Versace family. Eventually, assets had to be sold:

the Miami and New York houses, much of the artwork. Donatella and Mr.

Beck divorced. The company, after struggling, appears to be fiscally

sound.

Ten years on, I asked Mr. Filipowski what stands out in

his mind from that week.

He and his partner, Julie Mannion, were inside

the house the whole time, and Ms. Mannion had stayed with Versace’s

body in the morgue, at his sister’s request, until she and her brother

Santo could arrive from Italy.

Mr. Filipowski thought for a

moment and said: “How personal and private they kept everything — that’s

what I remember. With everything that was going on outside. It was:

‘Our brother is dead.’

No comments:

Post a Comment