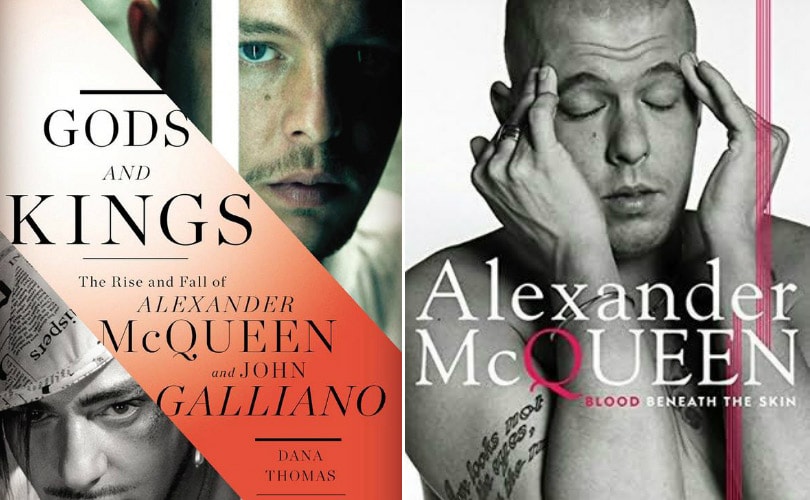

Alexander McQueen and John Galliano: forged in excess!

It seems fitting that two books celebrating – and analyzing – the influence of fashion gods Alexander McQueen and John Galliano should come out as the Oscars kick off the red carpet season. If anyone doubts the importance of these designers, they need only glance at the picture sections of both biographies to see their impact on Hollywood and beyond.

Here’s

Nicole Kidman in that incredible chartreuse Chinoiserie gown by Galliano

at the Academy Awards in 1997. Here’s Galliano at a Metropolitan Museum

of Art’s Costume Institute gala with the Princess of Wales wearing his

first official design for Dior in 1996. Here’s McQueen with Kate Moss,

Naomi Campbell, Helena Christensen and any other model you can think of.

McQueen might not have actually designed the most talked about red

carpet dress of the 21st century but he lent his name to it when Kate

Middleton chose his successor Sarah Burton to design her wedding dress,

the year following his death.

That

said, as Dana Thomas makes clear in Gods and Kings, the glossy surface

is only a small part of the story. Thomas, a style writer for The

Washington Post and Newsweek, has spoken to more than 100 fashion

insiders to put together a portrait of an era dominated, in her account,

by these two uncontrollable and wild talents. Her story can be read as a

bitter criticism of the fashion world: she depicts both designers as

fiercely self-destructive, and working in an industry where that was

encouraged, indulged and exploited.

She charts the “fashion moment” defined by Galliano and McQueen from

Galliano’s St Martins graduation show in 1984 (a crazed riot of French

Revolution-inspired dandies with candyfloss hair and red, white and blue

rosettes) to McQueen’s suicide in February 2010 and Galliano’s

dismissal from the house of Dior a year later. (He was fired for making

anti-semitic remarks.) During this period the fashion industry was

transformed. “When Galliano first started back in the mid-Eighties, he

produced two collections annually. At the time of his termination in

2011, he was overseeing – at the Dior and John Galliano brands combined –

an astounding 32 collections a year.” It’s not a recipe for mental

stability.

Thomas’s narrative flits

deftly between the “parallel professional journeys” of two men with a

similar rebellious streak. Galliano was born in Gibraltar and raised in

south London, his father a plumber, his mother a flamenco teacher.

McQueen was brought up in Lewisham, his mother also a teacher, his

father a taxi driver. Both were driven to celebrate and escape their

class: proud of their roots but also surrounding themselves with people

from the opposite end of the spectrum.

What’s interesting about Thomas’s account is that she doesn’t shy

away from the nasty bits: she paints both Galliano and McQueen as

intensely difficult people – bullying, drug-abusing narcissists. But she

also brings out the benefits of a designer’s capricious nature: these

people create “moments” and bring the wow factor.

On the hunt

for a successor for Galliano at Dior (now filled by Raf Simons), one

source tells Thomas that the stakes have got too high now that fashion

has become corporate: “Dior is a serious business, and they are

permanently turned in circles around what to do. They are afraid. Really

afraid. There is too much money in play.” Fashion, she concludes, “has

grown into a monolith that has no time or patience for imaginative young

designers”. Now there is “no poetry, no heart”.

Andrew Wilson’s

heartbreaking biography of McQueen takes an unflinching look at the

personal price McQueen paid for this supposed poetry. This seems like a

fan’s book at first glance – “written with the support of the McQueen

family” – but it’s a wonderfully readable and well-researched account.

There is plenty to gawp at. McQueen had a death wish in terms of both

drugs and tantrums. The tale of his friendship with Isabella Blow, the

aristocrat stylist who “discovered” him, is emblematic of many episodes

in his life: crazed passion and obsession intermingled with abuse and

hatred.

“There was some sort of psychosexual relationship between the

two of them. She was completely enamoured of him and his work, and I

think he wanted to punish her.” He once made fun of her by cutting two

holes in a muslin bag and giving it to her as a dress. “I love this,

darling!” she cooed. He burst out laughing as soon as she left the room.

Wilson paints McQueen as an intensely complex but ultimately

likeable person with a dark side that eventually destroyed him. The way

the story is told, there is a certain inevitability to McQueen’s fate.

But it seems deeply tragic that he killed himself a week after his

mother’s death, three years after the suicide of his one-time mentor

Blow.

Despite all the outrageous episodes, Wilson’s coup is to

make McQueen seem human, tortured by his genius. Both books give the

impression that the fashion industry is good at allowing people to be

bonkers, but then doesn’t know what to do with them. It almost makes

unpoetic commercialism seem tempting.

No comments:

Post a Comment