Death by Design

It all happend in 1996 the month of May,when High Fashion Muse and Model plunged from her window 18 years ago. I have always be admiring the work of Montana and his details of the garments, shoulder pads, the futuristic styles and the looks .

After a shocking news of where in the world is Claude Montana...Recently found an article by the Vanity Fair from 1996. And yes, more shocking news of his wife!

High-fashion muse and model Wallis Franken Montana plunged from the kitchen window of her Rue de Lille apartment in May, leaving the Paris couture world in a state of shock. The author investigates Montana’s tormented relationship with her husband, designer Claude Montana, the abusive “dark angel” who friends and family believe played a part in the American beauty’s death.

The article written by Maureen Orth for Vanity Fair.

The Paris photographer called to say that he would like to take a family portrait. Wallis Franken Montana, the vivacious American former model popular in the haute world of French fashion and married to designer Claude Montana, thought that meant he wanted her to pose with her two grown daughters from a former liaison and her two grandchildren. But the photographer had something else in mind, Wallis later confided to a friend. He told her he wanted to shoot her with Claude, Claude’s latest boyfriend, and the new young fitting model who Wallis feared might be taking her place with the mercurial designer.

In the three years since she had married the hard-partying and openly gay Montana in a wedding that stunned even the normally blasé fashion world, Wallis Franken had endured terrible physical and emotional abuse from her complicated and unconventional husband. Friends had begged her to leave him, but she told them that she was “obsessed” with Montana. She had been his muse and his ally since he started out in the mid-70s, and she thought of him not only as a genius but also as her alter ego.

“He’s was sort of like her fate, her dark angel,” says Wallis’s friend Maxime de la Falaise. “She’d been in love with Claude for years.” Yet after decades of putting up with all the men and the nocturnal comings and goings in Montana’s life—not to mention his jealousy and possessiveness of her—the addition of the young fitting model, at a time when Wallis told friends Montana was ridiculing her as “old and ugly,” seemed particularly rattling.

“Isn’t that weird?” she asked her friend Carolyn Schultz about the photographer’s request a few days before she returned to Paris from New York last May. But nobody, not even her family, seemed to have the slightest inkling of the depth of her despair. As usual, Wallis managed to fool everybody.

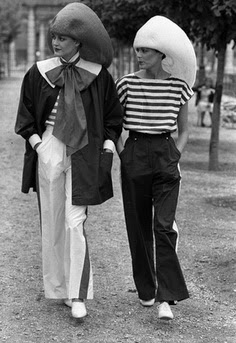

With her Louise Brooks bob, her lithe, androgynous body, and her raucous laugh, Wallis Franken was celebrated for her taste and style, but even more for her sparkling, care-free nature. To the sophisticates of Paris’s couture world, who knew her so well, she was never in a bad mood, but always warm, full of ideas, and ready for a good time. “She did not have the personality of a model but of a woman,” says designer Hervé Léger. “We do not find what she had in girls now. She became a real Parisienne. Even though we all know she didn’t have an easy time, I never saw her anxious or depressed. Wallis projected crème fraîche.”

Because she had natural chic and a creative spark, she became a muse not only to Montana but also to designers Michel Klein and Fernando Sanchez in New York.

“If you put your clothes on Wallis, you’d know immediately if it was right,” says Sanchez. “She had an innate sense of elegance,” says Loulou de la Falaise, daughter of Maxime. “When working with friends she admired, she was like a brilliant editor—neat, sharp, supportive.”

Wallis was a fabulous cook and possessed a good enough singing voice to record the hit “Étrange Affaire” in 1984. Music was also a cover for sadness. “You’d talk about something heavy and she’d answer with a song—‘I’m singing in the rain’ or ‘Good morning heartache,’” says Paris nightclub impresario Guy Cuevas. “She liked bubbles. We were nightclubbers—we wore bubbles so well.”

Her heyday on the runway was in the 70s, before the era of the supermodel, when lucrative product-endorsement contracts were rare. But at 48 she remained a fixture on the fashion scene, still able to wow them last March at Montana’s show at the Institute of the Arab World on the Left Bank.

“You could see her person—there was a vulnerability in those eyes. How many models actually reveal that?” says Mark Van Amringe of Details magazine’s Paris office. “Wallis was the first mannequin to give the impression that the image belonged to her, not to the couturier,” says Christian Lacroix’s business partner, Jean-Jacques Picart. “She became an international figure.”

In late April and early May, Wallis spent a wonderful two weeks in New York, tending to her aging mother, seeing old friends, buying gifts for Montana, and visiting a Chinese herbalist, to whom she recited a litany of menopausal symptoms. She told him, for example, that unstoppable tears would sometimes flow from her eyes, but she never mentioned the possibility of depression. She said she was excited that her daughter, Rhea, 26, who had two small daughters, was about to give birth to a grandson. “She left in very high spirits,” says Sanchez. Wallis made a date to meet Sanchez three weeks later at his house in Marrakech. Then she flew home, arriving on Monday morning, May 6.

She spent Tuesday at Montana’s boutique on Avenue Marceau, playing host to a German TV crew, choosing outfits for the young fitting model to pose in, treating the visitors to jokes and champagne. Her younger daughter, Celia, 24, who worked at the boutique, was also on hand to help out. “She smiled a lot and talked to everybody,” says the TV producer, Alexandra von Schledorn. She and Montana were polite and careful with each other.

Nobody saw her on Wednesday, yet it was not unusual for her to take to her bed for 24 hours at a time. Neighbors who had previously complained to the police of loud music and rows emanating from Montana’s apartment on the Rue de Lille in the chic Seventh Arrondissement didn’t bother to look out to the back courtyard in the early morning hours when they heard a kind of thump. It wasn’t until seven hours later, on Thursday, May 9, that Wallis Franken’s bloodied body was discovered splattered on the cobblestones. She was wearing black leggings, socks, and a white shirt that was torn—a detail reportedly of interest to the Paris police.

The concierge could not even tell who she was. She had apparently taken a swan dive out the second-story kitchen window, a drop of 25 feet. The police, who woke Montana to make the identification, questioned him for hours. They found her jewelry lined up neatly on the kitchen table. Montana apparently told the police as well as Wallis’s family that he had felt a draft during the night and had closed the kitchen window, but had not looked outside. He said the last time he saw Wallis alive was in the wee hours of Wednesday, May 8, when she fell asleep on the living-room sofa. By the time he left for work that day, she had moved to her own room, or so he assumed. He did not check. Nor did he bother to look in on her Wednesday night when he returned.

The body was not removed from the courtyard until midafternoon. After an autopsy, which showed no marks or signs of self-defense on her body but which did show that she had ingested alcohol and cocaine, the French authorities have officially ruled Wallis Franken’s death a suicide by defenestration. Her family accepts that verdict. Nevertheless, her older brother Randy, who lives in Germany, and her mother, who lives in New York, both gave statements to the French police. They also engaged a lawyer who, according to Randy Franken, “made clear to authorities that there was a history of abuse.”

What convinced Randy that his sister took her own life, however, was the height of the kitchen window. “I’m six foot three, and the sill hits me at my chest. If you wanted to push someone out, it would be a real job.” But these facts have not stopped the distraught and incredulous friends of Wallis Franken from blaming the diminutive Claude Montana for contributing to her death.

‘I feel that no matter what Claude did, whether his hands were on her or not, the lifestyle he gave her, the way he abused her mentally, emotionally, physically, pushed her over the edge,” says Wallis’s closest friend, former model turned painter Tracey Weed. “I have no doubt that he was a contributing factor to my sister’s demise, perhaps a major contributing factor,” says Randy Franken. “We all have the same idea,” echoes painter Vincent Scali, Wallis’s witness at her marriage to Montana. “Everybody knew that his part in her death was enormous.” How did Montana contribute? “By treating her like shit, saying, ‘You’re no one, you’re nobody, you’re a weight on my life.’ … He knew Wallis was weak.… We did everything in our power to keep her away from him, and she went back. She was a masochist.”

In the three years since she had married the hard-partying and openly gay Montana in a wedding that stunned even the normally blasé fashion world, Wallis Franken had endured terrible physical and emotional abuse from her complicated and unconventional husband. Friends had begged her to leave him, but she told them that she was “obsessed” with Montana. She had been his muse and his ally since he started out in the mid-70s, and she thought of him not only as a genius but also as her alter ego.

“He’s was sort of like her fate, her dark angel,” says Wallis’s friend Maxime de la Falaise. “She’d been in love with Claude for years.” Yet after decades of putting up with all the men and the nocturnal comings and goings in Montana’s life—not to mention his jealousy and possessiveness of her—the addition of the young fitting model, at a time when Wallis told friends Montana was ridiculing her as “old and ugly,” seemed particularly rattling.

“Isn’t that weird?” she asked her friend Carolyn Schultz about the photographer’s request a few days before she returned to Paris from New York last May. But nobody, not even her family, seemed to have the slightest inkling of the depth of her despair. As usual, Wallis managed to fool everybody.

With her Louise Brooks bob, her lithe, androgynous body, and her raucous laugh, Wallis Franken was celebrated for her taste and style, but even more for her sparkling, care-free nature. To the sophisticates of Paris’s couture world, who knew her so well, she was never in a bad mood, but always warm, full of ideas, and ready for a good time. “She did not have the personality of a model but of a woman,” says designer Hervé Léger. “We do not find what she had in girls now. She became a real Parisienne. Even though we all know she didn’t have an easy time, I never saw her anxious or depressed. Wallis projected crème fraîche.”

Because she had natural chic and a creative spark, she became a muse not only to Montana but also to designers Michel Klein and Fernando Sanchez in New York.

“If you put your clothes on Wallis, you’d know immediately if it was right,” says Sanchez. “She had an innate sense of elegance,” says Loulou de la Falaise, daughter of Maxime. “When working with friends she admired, she was like a brilliant editor—neat, sharp, supportive.”

Wallis was a fabulous cook and possessed a good enough singing voice to record the hit “Étrange Affaire” in 1984. Music was also a cover for sadness. “You’d talk about something heavy and she’d answer with a song—‘I’m singing in the rain’ or ‘Good morning heartache,’” says Paris nightclub impresario Guy Cuevas. “She liked bubbles. We were nightclubbers—we wore bubbles so well.”

Her heyday on the runway was in the 70s, before the era of the supermodel, when lucrative product-endorsement contracts were rare. But at 48 she remained a fixture on the fashion scene, still able to wow them last March at Montana’s show at the Institute of the Arab World on the Left Bank.

“You could see her person—there was a vulnerability in those eyes. How many models actually reveal that?” says Mark Van Amringe of Details magazine’s Paris office. “Wallis was the first mannequin to give the impression that the image belonged to her, not to the couturier,” says Christian Lacroix’s business partner, Jean-Jacques Picart. “She became an international figure.”

Nobody saw her on Wednesday, yet it was not unusual for her to take to her bed for 24 hours at a time. Neighbors who had previously complained to the police of loud music and rows emanating from Montana’s apartment on the Rue de Lille in the chic Seventh Arrondissement didn’t bother to look out to the back courtyard in the early morning hours when they heard a kind of thump. It wasn’t until seven hours later, on Thursday, May 9, that Wallis Franken’s bloodied body was discovered splattered on the cobblestones. She was wearing black leggings, socks, and a white shirt that was torn—a detail reportedly of interest to the Paris police.

The concierge could not even tell who she was. She had apparently taken a swan dive out the second-story kitchen window, a drop of 25 feet. The police, who woke Montana to make the identification, questioned him for hours. They found her jewelry lined up neatly on the kitchen table. Montana apparently told the police as well as Wallis’s family that he had felt a draft during the night and had closed the kitchen window, but had not looked outside. He said the last time he saw Wallis alive was in the wee hours of Wednesday, May 8, when she fell asleep on the living-room sofa. By the time he left for work that day, she had moved to her own room, or so he assumed. He did not check. Nor did he bother to look in on her Wednesday night when he returned.

The body was not removed from the courtyard until midafternoon. After an autopsy, which showed no marks or signs of self-defense on her body but which did show that she had ingested alcohol and cocaine, the French authorities have officially ruled Wallis Franken’s death a suicide by defenestration. Her family accepts that verdict. Nevertheless, her older brother Randy, who lives in Germany, and her mother, who lives in New York, both gave statements to the French police. They also engaged a lawyer who, according to Randy Franken, “made clear to authorities that there was a history of abuse.”

‘I feel that no matter what Claude did, whether his hands were on her or not, the lifestyle he gave her, the way he abused her mentally, emotionally, physically, pushed her over the edge,” says Wallis’s closest friend, former model turned painter Tracey Weed. “I have no doubt that he was a contributing factor to my sister’s demise, perhaps a major contributing factor,” says Randy Franken. “We all have the same idea,” echoes painter Vincent Scali, Wallis’s witness at her marriage to Montana. “Everybody knew that his part in her death was enormous.” How did Montana contribute? “By treating her like shit, saying, ‘You’re no one, you’re nobody, you’re a weight on my life.’ … He knew Wallis was weak.… We did everything in our power to keep her away from him, and she went back. She was a masochist.”

No comments:

Post a Comment