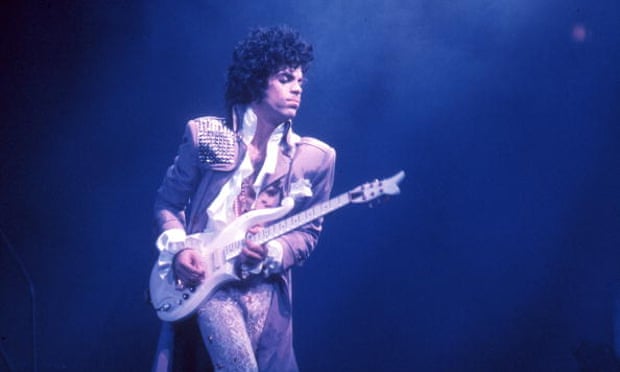

Prince,

the songwriter, singer, producer, one-man studio band and consummate

showman, died on Thursday at his home, Paisley Park, in Chanhassen,

Minn. He was 57.

His

publicist, Yvette Noel-Schure, confirmed his death but did not report a

cause. In a statement, the Carver County sheriff, Jim Olson, said that

deputies responded to an emergency call at 9:43 a.m. “When deputies and

medical personnel arrived,” he said, “they found an unresponsive adult

male in the elevator. Emergency medical workers attempted to provide

lifesaving CPR, but were unable to revive the victim. He was pronounced

deceased at 10:07 a.m.”

The sheriff’s office said it would continue to investigate his death.

Last

week, responding to news reports that Prince’s plane had made an

emergency landing because of a health scare, Ms. Noel-Schure said Prince

was “fighting the flu.”

Prince

was a man bursting with music — a wildly prolific songwriter, a

virtuoso on guitars, keyboards and drums and a master architect of funk,

rock, R&B and pop, even as his music defied genres. In a career

that lasted from the late 1970s until his solo “Piano & a

Microphone” tour this year, he was acclaimed as a sex symbol, a musical

prodigy and an artist who shaped his career his way, often battling with

accepted music-business practices.

Prince sold more than 100 million records, won seven Grammys and was inducted Hall of Fame.

A

seven-time Grammy winner, Prince’s Top 10 hits included “Little Red

Corvette,” “When Doves Cry,” “Let’s Go Crazy,” “Kiss” and “The Most

Beautiful Girl in the World”; albums like “Dirty Mind,” “1999” and “Sign

O’ the Times” were full-length statements. His songs also became hits

for others, among them “Nothing Compares 2 U” for Sinead O’Connor,

“Manic Monday” for the Bangles and “I Feel for You” for Chaka Khan. With

the 1984 film and album “Purple Rain,”

he told a fictionalized version of his own story: biracial, gifted,

spectacularly ambitious. Its music won him an Academy Award, and the

album sold more than 13 million copies in the United States alone.

In

a statement, President Obama said, “Few artists have influenced the

sound and trajectory of popular music more distinctly, or touched quite

so many people with their talent.”

He

added, “He was a virtuoso instrumentalist, a brilliant bandleader, and

an electrifying performer. ‘A strong spirit transcends rules,’ Prince

once said — and nobody’s spirit was stronger, bolder, or more creative.”

Prince

recorded the great majority of his music entirely on his own, playing

every instrument and singing every vocal line. Many of his albums were

simply credited, “Produced, arranged, composed and performed by Prince.”

Then, performing those songs onstage, he worked as a bandleader in the

polished, athletic, ecstatic tradition of James Brown, at once

spontaneous and utterly precise, riveting enough to open a Grammy Awards

telecast and play the Super Bowl Halftime show. He would often follow a full-tilt arena concert with a late-night club show, pouring out even more music.

On

Prince’s biggest hits, he sang passionately, affectionately and

playfully about sex and seduction. With deep bedroom eyes and a sly,

knowing smile, he was one of pop’s ultimate flirts: a sex symbol devoted

to romance and pleasure, not power or machismo. Elsewhere in his

catalog were songs that addressed social issues and delved into

mysticism and science fiction. He made himself a unifier of dualities —

racial, sexual, musical, cultural — teasing at them in songs like

“Controversy” and transcending them in his career.

He

had plenty of eccentricities: his fondness for the color purple, using

“U” for “you” and a drawn eye for “I” long before textspeak, his

vigilant policing of his music online, his penchant for releasing troves

of music at once, his intensely private persona. Yet for musicians and

listeners of multiple generations, he was admired well-nigh universally.

Prince’s

music had an immediate and lasting influence: among songwriters

concocting come-ons, among producers working on dance grooves, among

studio experimenters and stage performers. He sang as a soul belter, a

rocker, a bluesy ballad singer and a falsetto crooner. His most

immediately recognizable (and widely imitated) instrumental style was a

particular kind of pinpoint, staccato funk, defined as much by keyboards

as by the rhythm section. But that was just one among the many styles

he would draw on and blend, from hard rock to psychedelia to electronic

music. His music was a cornucopia of ideas: triumphantly, brilliantly

kaleidoscopic.

Prince

Rogers Nelson was born in Minneapolis on June 7, 1958, the son of John

L. Nelson, a musician whose stage name was Prince Rogers, and Mattie

Della Shaw, a jazz singer who had performed with the Prince Rogers Band.

They were separated in 1965, and his mother remarried in 1967. Prince

spent some time living with each parent and immersed himself in music,

teaching himself to play his instruments. “I think you’ll always be able

to do what your ear tells you,” he told his high school newspaper,

according to the biography “I Would Die 4 U: Why Prince Became an Icon”

(2013) by the critic Touré.

Eventually

he ran away, living for some time in the basement of a neighbor whose

son, André Anderson, would later record as André Cymone. As high school

students they formed a band that would also include Morris Day, later

the leader of the Time. In classes, Prince also studied the music

business.

He

recorded with a Minneapolis band, 94 East, and began working on his own

solo recordings. He was still a teenager when he was signed to Warner

Bros. Records, in a deal that included full creative control. His first

album, “For You” (1978), gained only modest attention. But his second,

“Prince” (1979), started with “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” a No. 1 R&B

hit that reached No. 11 on the pop charts; the album sold more than a

million copies, and for the next two decades Prince albums never failed

to reach the Top 100. During the 1980s, nearly all were million-sellers

that reached the Top 10.

With

his third album, the pointedly titled “Dirty Mind,” Prince moved from

typical R&B romance to raunchier, more graphic scenarios; he posed

on the cover against a backdrop of bedsprings and added more rock guitar

to his music. It was a clear signal that he would not let formats or

categories confine him. “Controversy,” in 1981, had Prince taunting, “Am

I black or white?/Am I straight or gay?” His audience was broadening;

the Rolling Stones chose him as an opening act for part of their tour

that year.

Prince

grew only more prolific. His next album, “1999,” was a double LP; the

video for one of its hit singles, “Little Red Corvette,” became one of

the first songs by an African-American musician played in heavy rotation

on MTV. He was also writing songs with and producing the female group

Vanity 6 and the funk band Morris Day and the Time, which would have a

prominent role in “Purple Rain.”

Prince

played “the Kid,” escaping an abusive family to pursue rock stardom, in

“Purple Rain.” Directed by Albert Magnoli on a budget of $7 million, it

was Prince’s film debut and his transformation from stardom to

superstardom. With No. 1 hits in “Let’s Go Crazy” and “When Doves Cry,”

he at one point in 1984 had the No. 1 album, single and film

simultaneously.

He

also drew some opposition. “Darling Nikki,” a song on the album that

refers to masturbation, shocked Tipper Gore, the wife of Al Gore, who

was then a United States senator, when she heard her daughter listening

to it, helping lead to the formation of the Parents’ Music Resource

Center, which eventually pressured record companies into labeling albums

to warn of “explicit content.” Prince himself would later, in a more

religious phase, decide not to use profanities onstage, but his songs —

like his 2013 single “Breakfast Can Wait” — never renounced carnal

delights.

Prince

didn’t try to repeat the blockbuster sound of “Purple Rain,” and for a

time he withdrew from performing. He toyed with pastoral, psychedelic

elements on “Around the World in a Day” in 1985, which included the hit

“Raspberry Beret,” and “Parade” in 1986, which was the soundtrack for a

movie he wrote and directed, “Under the Cherry Moon,” that was an

awkward flop. He also built his studio complex, Paisley Park, in the

mid-1980s for a reported $10 million, and in 1989 his “Batman”

soundtrack album sold two million copies.

Friction

grew in the 1990s between Prince and his label, Warner Bros., over the

size of his output and how much music he was determined to release.

“Sign O’ the Times,” a monumental 1987 album that addressed politics and

religion as well as romance, was a two-LP set, cut back from a triple.

By

the mid-1990s, Prince was in open battle with the label, releasing

albums as rapidly as he could to finish his contract; quality suffered

and so did sales. He appeared with the word “Slave” written on his face,

complaining about the terms of his contract, and in 1993 he changed his

stage name to an unpronounceable glyph, only returning to Prince in

1996 after the Warner contract ended. He marked the change with a triple

album, independently released on his own NPG label: “Emancipation.”

For

the next two decades, Prince put out an avalanche of recordings.

Hip-hop’s takeover of R&B meant that he was heard far less often on

the radio; his last Top 10 hit was “The Most Beautiful Girl in the

World,” in 1994. He experimented early with online sales and

distribution of his music, but eventually turned against what he saw as

technology companies’ exploitation of the musician; instead, he tried

other forms of distribution, like giving his 2007 album “Planet Earth”

away with copies of The Daily Mail in Britain. His catalog is not

available on the streaming service Spotify, and he took extensive legal

measures against users of his music on YouTube and elsewhere.

But

Prince could always draw and satisfy a live audience, and concerts

easily sustained his later career. He was an indefatigable performer:

posing, dancing, taking a turn at every instrument, teasing a crowd and

then dazzling it. He defied a downpour to play a triumphal “Purple Rain”

at the Super Bowl halftime show in 2007, and he headlined the Coachella

festival in 2008 for a reported $5 million. A succession of his bands —

the Revolution, the New Power Generation, 3rdEyeGirl — were united by

their funky momentum and quick reflexes as Prince made every show seem

both thoroughly rehearsed and improvisational.

A trove of Prince’s recordings remains unreleased, in an archive he called the Vault.

Like much of his offstage career, its contents are a closely guarded

secret, but it’s likely that there are masterpieces yet to be heard.